The Placeholder: the Tween Stage of Adulthood

How to Guide Yourself in the Placeholder Determines the Quality of Your Midlife

Observing the emotional, cognitive, and relational transitions my daughter is going through in her tween stage (age 9 and 12), I can tell she’s on the path to be inducted to adolescence. At times, she acts like an adolescent, arguing about every instruction I give to her; yet she still comes to my room and kisses on my cheek, completely unprompted. Frankly, I’m more confused than ever how to treat her. What is odd to me is that this tween stage doesn’t get proper treatment like other life stages, although it seems like a pretty critical liminal phase between childhood and adolescence.

The tween didn’t get formally recognized as a distinct developmental stage in developmental psychology, unlike childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood. Instead, it just got a cute nickname “tween”, a blend of “teen” and “between”. Not quite children, yet not teenagers, tweens are in the liminal space to adolescence and no one (including themselves and their parents) exactly knows what to do.

I’d say the life stage between the age 30 and 45 is equivalent to this tween phase in adulthood. Broadly termed as “middle age”, we are expected to know what we ought to do for our career, relationships, or any other major life decisions. Way past early adulthood, we cannot be “immature” nor “naive” anymore. Although labeled as a middle age, we don’t feel quite “established” or “wise enough” yet to claim the full maturity. It’s also too early to expect a midlife crisis. We are in a liminal space in our midlife.

However, like tweens, we start experiencing significant blows from the wind of transitions in this equivocal adulthood. That’s what happened to me and many people I interviewed in The Placeholder.

The Placeholder: Liminal Stage in Adulthood to Midlife

Nine years ago when I felt the sense of uneasiness growing in my mind like cancer around my thirty seventh birthday, I didn’t know what to do. Knowing that I was no longer twenty something and I couldn’t be having a midlife crisis yet, I just oscillated between ‘I shouldn’t feel this way; I should have my shi* together.’ and ‘What’s wrong with me?’

It was confusing like hell.

Having consumed all the old strategies and tactics to get me out of this funk, I had to part ways from the familiar and approach it in a completely different way. That was the beginning of my Placeholder.

What is a placeholder? Imagine a digital sign-up form, where placeholders appear inside input fields or text areas as faint text to provide an example of the type of information required (e.g., “Enter your name”). This text disappears once we start typing in the field.

The “Placeholder” phase in life serves the same purposes. It’s the phase of our life we enter to experiment new ideas because the old scripts and manuals no longer serve us or we don’t feel connected to it anymore.

This may apply to relationships, work, lifestyle, and communities we belong to. Particularly for work, it calls for a different kind of change. It’s not about finding a new job, moving to a new company or getting a promotion but about learning how to create the work that we truly find meaningful. The change with our work in the Placeholder is not something we find and strive to fit into. Rather, it’s a totally new approach we create that fits us.

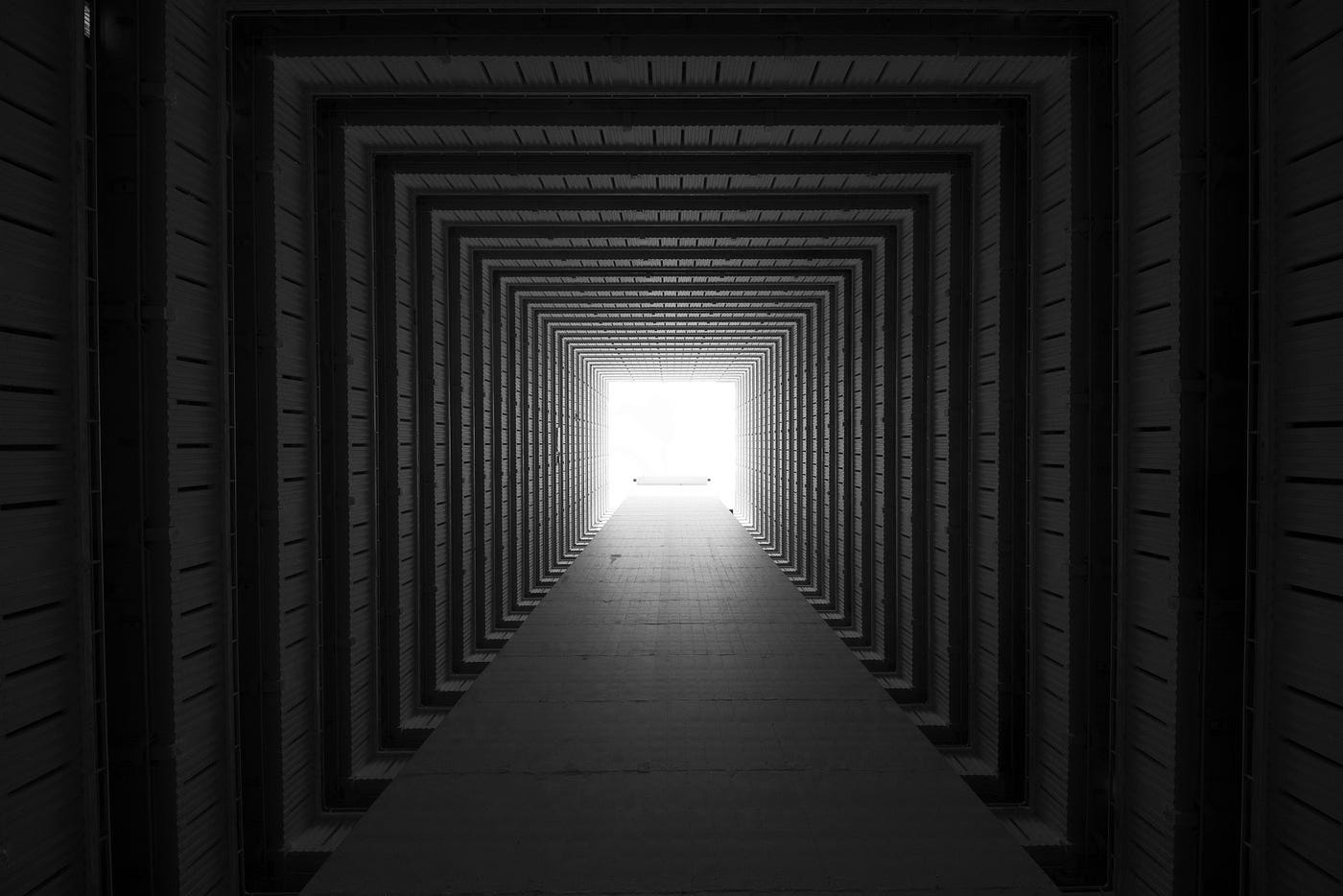

As the tween stage is like an introduction to adolescence, this Placeholder stage is the liminal adulthood that introduces us to the midlife. We are called to pause what we’ve been doing, reflect and warm up to the idea of breaking apart from old patterns. Then start trying completely new ideas. This is a necessary step for us, if we want to coagulate the midlife chrysalis, rather than crash into midlife crisis.

The Beginning of the Metamorphic Process

Chip Conley, the author and founder of Modern Elder Academy, describes the midlife as the chrysalis, the pupal stage of butterflies. Within this chrysalis, the transformational magic of metamorphosis occurs. He writes, “It is a bit dark and gooey, but it’s not a crisis but a transition. And, of course, on the other side is a beautiful, winged creature of elder hood.”

What’s worth noting is that the transformation begins even before a caterpillar becomes a chrysalis. A caterpillar stops eating and starts making a button of silk to fasten its body to a leaf or a twig. Then it sheds its skin and spins itself a silky cocoon, finally making itself into a shiny chrysalis.

That’s what happens in the Placeholder phase. Something feels off. It’s hard to pinpoint what is wrong, but we know subconsciously we cannot keep doing what we’ve been doing. Like a caterpillar stopping eating, we feel the urge to disrupt and start something anew. This seems counterintuitive at times, because we believe we have been on “the right track” for our career, relationships, and life in general. We start wondering what is “right” and questioning all the layers of identity we built about ourselves. It’s unsettling, scary, and debilitating. It’s the “Nigredo” time, the first stage of alchemy.

The general principle of alchemy is Solvey et Coagula, which means to dissolve and coagulate or to have things fall apart and reform. Alchemists believed that the core of the material was essentially perfect. However, around this pure and perfect core, all the constructs and wrong stuff have encrusted. So the idea in alchemy is to break apart those false qualities that’s built around the core in order to dissolve them. As a result, eventually the “Philosopher’s Stone” is created out of the little pieces that are fallen apart from the old “self”.

Nigredo is the very first stage of this entire alchemical process. It means “blackening”, symbolizing the process of breaking down the old self or material to its most pure and basic state. Psychologically, this suggests facing the shadow, confronting inner darkness, and the disintegration of all the egos we constructed in our life so far.

Like what caterpillars do to turn itself into a chrysalis and what alchemists do to let the substance drop all kinds of impurities in the Nigredo stage, it seems inevitable to go through the painstaking process of the Placeholder so we can mature into our midlife.

But You Don’t Have to Suffer

It’s unarguably full of uncertainties to drop our old identities and try new ideas. This can be painful financially, emotionally, and cognitively. But the reason I wrote The Placeholder started from this question, “Do we need to suffer from going through this liminal stage?” In my own experience and through the cases of others, the answer was, “Not really.” Suffering could be optional if we are willing to approach this phase with new perspectives of an anthropologist, a creative designer, and a mad scientist.

Like an anthropologist, we observe and learn more about the new need of ourselves patiently. Like a creative designer, we ideate, ideate, and ideate without putting limits on ourselves. And like a mad scientist, we experiment those ideas, learn from them, and repeat.

It’s definitely easier said than done and the process is much messier than what we can imagine but the stories of people whom I call “Placeholder Wayfinders” are proofs that we can save ourselves from suffering in the Placeholder.

Restoring the Agency in the Placeholder

To my confusion not knowing how to treat my tween daughter, a wise person advised recently, “Let her know in which life stage she’s in and ask her, ‘How would you like to be treated? What would serve you best?’” This was such a great advice because not only I could get some guidance from her but also it would empower her with a sense of agency. As much as I am confused as a parent, I am sure she’s equally or even more puzzled about her transition toward adolescence. It is critical for her to restore the agency.

This also applies to us in the Placeholder, too. By simply acknowledging that we are entering a significant metamorphic process in our adulthood, we stop berating ourselves, asking “What’s wrong with me?” Instead, we glide into this beginning process of alchemy and metamorphosis called “midlife” with curiosity, creativity, and courage by being an anthropologist, designer, and mad scientist. Then we can finally feel at ease and peace with every transition to come.

What else could be more gratifying than being able to go through change with ease and peace in life? As the psychologist Carl Rogers wrote, “The good life is a process, not a state of being,” this is how we can live a good life.